FOCUS SCIENTIFICO – Prove di resistenza al fuoco: Cigarette Test

Le prove di resistenza al fuoco sono utilizzate per valutare il comportamento all’accensione dei materiali,…

FORMAZIONE: L’azienda Melluso in visita alla SSIP: collaborazione per Formazione, Ricerca e Sviluppo

L'azienda Melluso in visita alla SSIP: ospiti della Stazione Sperimentale nella sede di Pozzuoli, Alessandro…

RIVISTA – STYLE MPA – Dicembre 2025

◊ Letture presso la Biblioteca della Stazione Sperimentale Pelli ◊ Rivista di settore: Style Tannery International …

LEATHER UPDATE N. 2/2026

Pubblicata la nostra Leather Update con notizie, focus scientifici e curiosità dal mondo della pelle…

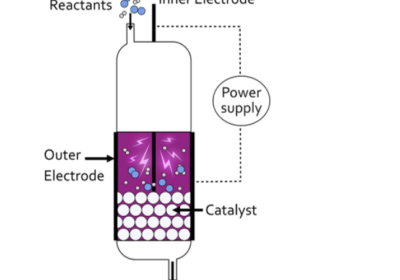

Focus Scientifico – Le proprietà attivanti del plasma non termico

Il plasma atmosferico (non-termico) è una miscela di gas parzialmente ionizzato generato da una scarica…

CDA SSIP: BALDUCCI CONFERMATO PRESIDENTE, VICE LA BACCHI ED ENTRA DE PASCALE

Nuova composizione per il Consiglio di Amministrazione della Stazione Sperimentale per l'Industria delle Pelli, che…

MAGAZINE – CTC Entreprises dic-genn. 2026

◊ Letture presso la Biblioteca della Stazione Sperimentale Pelli ◊ Rivista di settore: CTC entreprises Questa rivista,…

DA CPMC – Cassano: “La tecnologia a membrana come approccio sostenibile nelle produzioni conciarie secondo una visione circolare”

Le operazioni a membrana, come la microfiltrazione (MF), l’ultrafiltrazione (UF), la nanofiltrazione (NF) e l’osmosi…

LEATHER UPDATE N. 1/2026

Pubblicata la nostra Leather Update con notizie, focus scientifici e curiosità dal mondo della pelle…

Focus Scientifico – La mappatura delle sostanze critiche sui reflui conciari / Parte 2

Lo studio sulla mappatura delle sostanze critiche conciarie inquinanti, nell’ambito del progetto REWASTER, prosegue in…